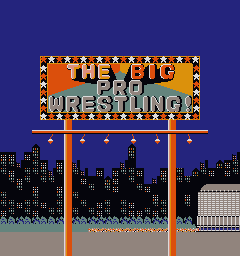

Technically, this isn’t the first ever pro-wrestling video game (it appears that honour falls to the obscure The Puroresu, for Bandai’s short-lived 8-bit home computer, the RX-78 Gundam), but for most, The Big Pro Wrestling (known as Tag Team Wrestling in the west) is the place where it all started.

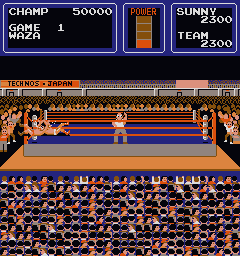

Developed by Technos Japan (and published by DataEast), this arcade game was released in Japan in December 1983 (3 months after The Puroresu). Of course, not only would Technos Japan go on to fame and fortune later in the 1980’s with the Kunio-kun (Renegade) series and Double Dragon, but wrestling fans will remember them for their subsequent arcade grapplers: Exciting Hour (Mat Mania) (1985), WWF SuperStars (1989) and WWF WrestleFest (1991).

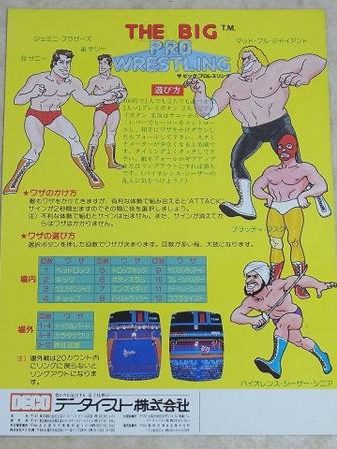

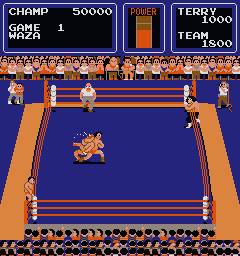

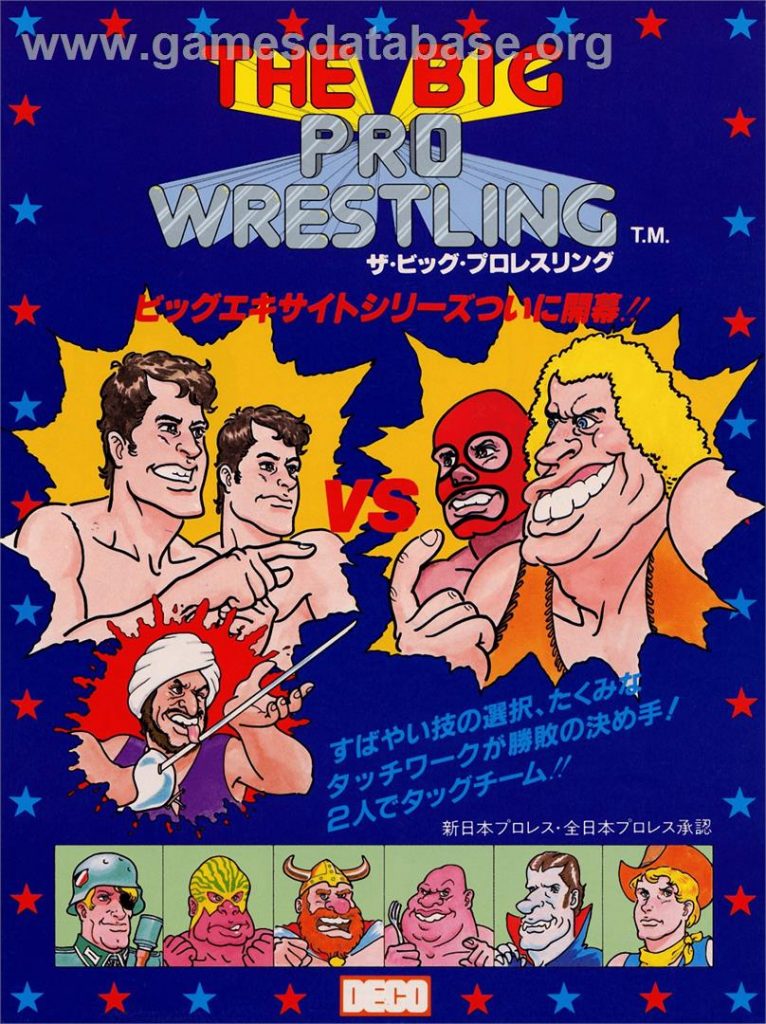

The game focuses solely on tag team matches and we are quickly introduced to the 4 main characters: the player-controlled Gemini Brothers (Terry and Sunny) and the CPU-controlled heels, Mad Bull Giant and Bloody Mask.

While clearly inspired by the likes of The Funks (Terry and Dory Jr), Andre the Giant and The Destroyer, the grapplers are arguably more like Japanese pro-wrestling archetypes rather than total clones of those real-life stars. In many ways, the babyface Gemini Brothers have more in common with legendary Japanese superstar Antonio Inoki than they do with the Funk Brothers.

There is less subtlety involved when the heels’ sword-wielding ally makes a rare appearance: the turban-wearing Violence Ceaser Singh is a very obvious knock-off of Tiger Jeet Singh.

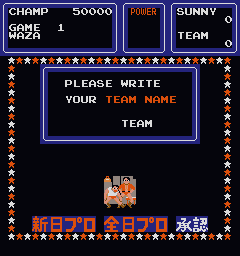

As you’ll have gathered from that cast of characters, The Big Pro Wrestling is unlicensed. However, curiously the name-entry screen (in both the Japanese and western releases) states that the game is “Approved by New Japan Pro and All Japan Pro“. The Japanese promotional flyer goes one further and makes clear that the approval comes from “New Japan Pro Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling“.

While it’s questionable whether any such approval was actually obtained (New Japan wouldn’t release a licensed game until 1991, with All Japan following suite in 1993), there’s really not much in the game that is connected to either company (other than the various Inoki-isms that are sprinkled throughout).

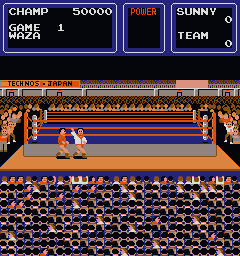

On that point, the Gemini Brothers go down in history as the first video game wrestlers to enjoy a ring-entrance, replete with theme music. They come out to a fairly obvious rendition of Mandrill / Michael Masser’s “Ali’s Theme / Ali Bombaye”, instantly recognizable to Japanese audiences as Inoki’s theme music.

Pre-match, the scene is further set with the presentation of flowers. As the ring announcer introduces the babyfaces, they throw their jackets into the air, while the dastardly heels whisper and plot in the other corner.

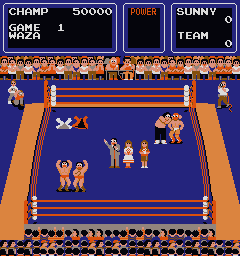

Throw in a packed and excitable crowd, the commentators at ringside, a pair of press photographers and a cameraman, and it all adds up to a charming representation of late 1970’s / early 1980’s Japanese pro-wrestling.

Then the bell sounds and away we go…

Gameplay

It’s worth remembering that, in late 1983, the fighting and beat-em up genres were still very much in their infancy.

The seminal Karate Champ (Karate Dō in Japan) wouldn’t be released for another 6 months and it would be a further 6 months before the snappy kicks and punches of Kung Fu Master (Spartan X) revolutionized the genre.

Therefore, even if Technos Japan had wanted to borrow heavily from existing fighting games of the time, there really was no template to follow. So, for better or worse, they ploughed their own furrow with The Big Pro Wrestling….

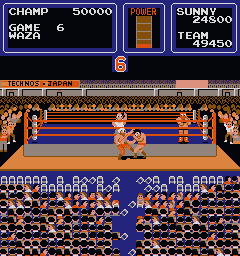

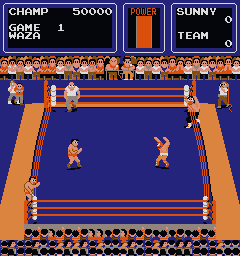

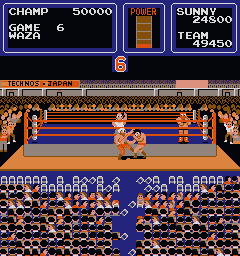

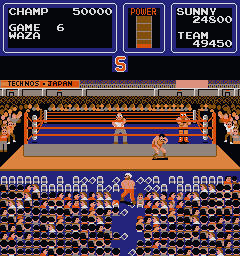

The action is viewed ‘side-on’, but at an elevated angle, giving a good view of the entire ring. When the bell rings, the joystick offers fluid 8-way movement of your wrestler. Again, it’s worth noting that there was no Renegade or Double Dragon at that point in time and such responsive mobility across the entire playing area (not only left and right, but also being able to control depth in the ring) would have been relatively novel.

However, while moving around, pressing either of the two action buttons does absolutely nothing: no strikes, no dashes, no grab animations.

Instead, both wrestlers (apparently randomly) raise their hands into the air at certain intervals – the hands remain aloft for a while, before dropping back down.

And this is the crux of the gameplay mechanism: if you maneuver yourself so that you collide with your opponent while your hands are up and theirs are down, you’ll have the advantage and can perform a grapple move (using a menu-based system).

In any other combination of “hands up / hands down”, we have a collar and elbow stalemate – with the player having to pull-away to attempt a re-engagement when the necessary “Player Hands Up” v “CPU Hands Down” situation occurs.

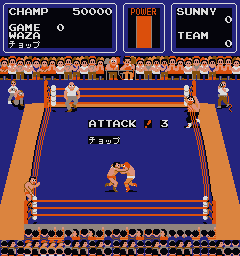

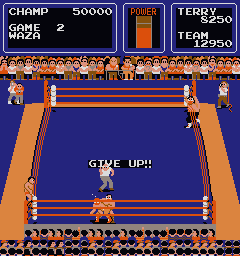

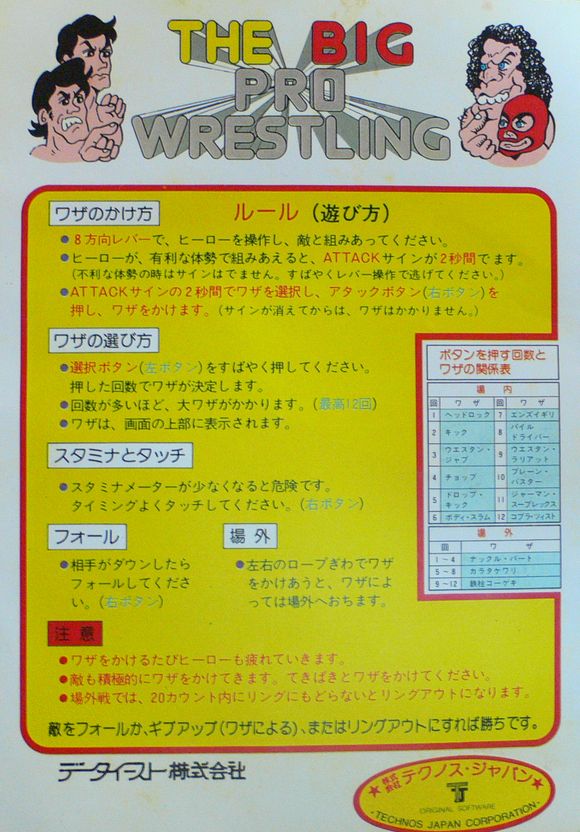

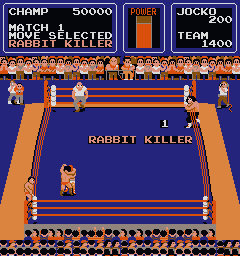

When you have the advantage in a grapple, a menu appears on screen. You then have 3 second countdown (2 seconds in “real time”) to tap the first button to cycle through the available moves, with each move in the list being more powerful than the last.

When you’ve highlighted a move that you like, pressing the second button performs the move. If the timer expires before you select a move, the opponent reverses the collar-and-elbow tie-up and slams you down. As such, the reward of going for the bigger moves (appearing later in the menu) is balanced against the risk of the timer expiring before you reach and select that move.

| Button Presses | Move |

|---|---|

| 0 | Headlock |

| 1 | Kick Combo |

| 2 | Western Jab |

| 3 | Chop Combo |

| 4 | Drop Kick |

| 5 | Body Slam |

| 6 | Enzui Giri |

| 7 | Piledriver |

| 8 | Western Lariat |

| 9 | Brainbuster |

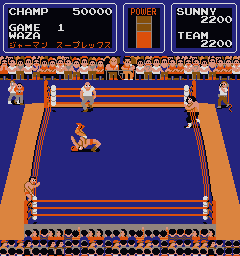

| 10 | German Suplex |

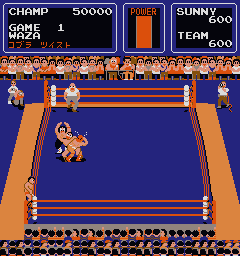

| 11 | Cobra Twist |

If you fail to lock-up with the CPU for a while (usually because you’re waiting for the perfect moment when your hands are up in the air, and theirs are down by their side), they fly into a rage (turning red) and at that point they zoom across the screen to catch you in an unavoidable and punishing grapple. As you get further into the game, the CPU affords you less and less time before activating this furious state.

A Power bar is displayed on screen showing your current wrestler’s heath. This not only depletes when you receive moves, but also reduces when you perform moves yourself, an early attempt at simulating stamina.

As the Power bar lowers, your movement speed slows. Tagging your partner allows you to recover some health on the apron, while the fresh man takes over in the ring.

Gameplay Hint

If you move downwards (towards the bottom of the screen), your arms will move to the opposite position: so if they’re down by your side when you’re facing left, right or upwards, they’ll be raised when you move downwards. You can use this (in conjunction with a ‘box-step’ technique) to maximise your chances of colliding with your opponent with your arms aloft

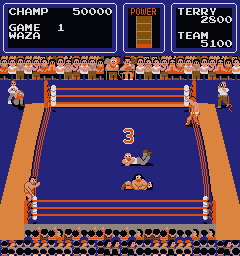

The move animations, while simplistic, would have been instantly recognizable to Japanese players: these include Terry Funk’s Western Jab combo, Antonio Inoki’s Enzuigiri and Cobra Twist, Stan Hansen’s Western Lariat, and the first appearance in a video game of a great Karl Gotch-inspired side-profile German Suplex. The crowd roars and sweat flies through the air as the moves connect, giving some visceral punch to proceedings.

The Drop Kick and Western Lariat (together with a number of the heels’ moves) have automated irish whip set-ups, with Technos Japan obviously keen to ensure that the pro-wrestling staple of running the ropes would feature in the game.

Interestingly, it’s also possible to achieve a submission victory by applying the Cobra Twist to Bloody Mask when his Power is low. Submission victories (as opposed to pinfall or count-out) are something that many later wrestling games wouldn’t even try to simulate. Of note too is the rudimentary ‘cut-play’ on show: attempt the Cobra Twist too early in the match and Mad Bull Giant will storm into the ring to break up the move.

The movesets for each member of the face team are identical, while the heels (who do not have to navigate the menu system) have their own selection of moves.

For the human player, attempting the more powerful moves (the Piledriver onwards) on the larger Mad Bull Giant character leads to an automatic reversal, so you need to chop him down with the smaller moves. Again, the first example of ‘weight detection’ in a wrestling game.

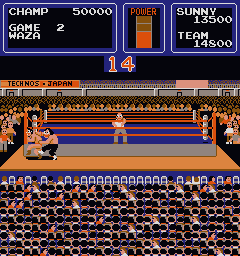

If a grapple move is performed near the ropes, the action can spill out to floor. At that point, not only does the view change, but the move-menu is reduced to three new moves: an Inoki-style Knuckle Arrow (or “Knuckle Part”) punch, a Giant Baba-style Brain Chop, and an attack where you ram your opponent into the ring post. Count-outs are possible and the CPU is not afraid to exploit that strategy.

In a fun twist, when you’re battling at ringside, there’s a chance that Violence Ceasar Singh will make an appearance. Rampaging through the crowd, he sends audience members and chairs flying before thrashing your hapless wrestler with his sword. It’s yet more evidence that the developers were true fans of Japanese pro-wrestling and it’s an impressive technical achievement – interference wouldn’t resurface in a wrestling game until 1989’s Fire Pro Wrestling Combination Tag.

When a wrestler is knocked down by a move, if the opponent doesn’t immediately attempt a pin, the downed wrestler quickly returns to their feet to re-commence the action (so there are no ground-grapples or prone-strikes). When the fallen wrestler has no Power left, their opponent automatically goes for a pinfall. In that situation, there are no kick-outs: the 3-count is inevitable.

If you win a match, you collect a trophy or belt (together with a point bonus depending on how quickly you secured the win) before you move on to the next match … against exactly the same opponents. The only difference is that the heels take turns starting the match as the legal man.

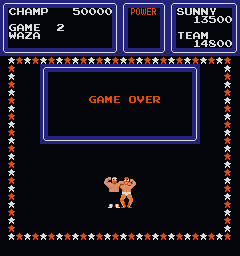

If you manage to achieve 10 wins in a row, you are crowned the “World Champion” (the news is delivered via some wholly underwhelming text on screen) but the matches keep coming in an endless loop.

Going back to presentation, the audio is pretty impressive for a game from 1983. Other than the aforementioned entrance music and some frenzied crowd noise, there is a smattering of synthesized speech to bring things to life. The heels shout “Come on!” at various intervals while your wrestler gives a very obvious Inoki-esque “Daa!” when he performs moves like Enzuigiris and Body Slams. The referee also gives an excitably high-pitched “one, two, THWEEEEE!” at the climax of the match (this same cadence would be re-used a couple of years later by the ref in Technos Japan’s Exciting Hour / Mat Mania).

Analysis

First and foremost, there’s no doubt that The Big Pro Wrestling is borne out of a love for Japanese pro-wrestling. The presentation evokes so much of that particular era: fans filing into the arena on a summer night, ring entrances, announcers, camera men, interference, cut play, and the classic tag team struggle between good and evil.

However, there’s also no doubt that the gameplay itself has not aged well. The key game mechanic involves you using the joystick to try to collide with your opponent while your hands are raised (and trying to avoid colliding them with them in any other circumstance).

In practice, you often end up in a stalemate position when you lock-up. You then have to quickly disengage and re-engage, hoping that the arm position of one or other of the wrestlers will be more favourable next time.

Even when exploiting that strategy, the AI becomes increasingly unreasonable and frustrating as the matches progress, flying into a rage before it’s possible to win a grapple.

The menu-based grapple system is also a limiting factor.

It’s an interesting solution to a key conceptual issue with wrestling games: how do you allow players to perform a wide variety of moves when you’re limited to a couple of buttons?

A menu system is perhaps an obvious (albeit crude) way around this problem. However, it’s unsurprising that Technos Japan abandoned it for their subsequent wrestling games (it would make a reappearance in Sega’s poor 1985 effort, Champion Pro-Wrestling, before disappearing). The aggression, struggle and drama of combat is poorly simulated when all you’re doing is selecting items from a menu. Even with the stress of a time-limit, it’s hardly high-octane action.

Also, rapidly tapping a button to scroll through a move-list usually means that you’re not really in control of the moves you perform: you might be aiming for a German Suplex, but you’re just as likely to hit a Cobra Twist, Brainbuster or Western Lariat, and you can find yourself accidentally repeating the same move over and over again.

Without any depth to the combat, the game becomes repetitive fairly quickly. With no variation between the matches, once you’ve won 3 or 4 in a row, there is little incentive to keep playing (unless of course you’re simply trying for a high score or attempting to win the title after 10 matches).

Other versions

An English translation, renamed Tag Team Wrestling (rather than “The Big Pro Wrestling”) was released in western arcades a month later in January 1984.

In this version, Sunny and Terry have become Jocko and Spike while the heels are rebranded as the Mad Maulers. Also, when translating the moves, they made some interesting choices (for example, “Enzuigiri” becomes “Rabbit Killer”) and there are some things they didn’t bother translating at all (e.g., the message saying that the game was approved by New Japan and All Japan remains in Japanese).

The difficulty appears to have been toned down slightly, with the player having a little more time to make their move selection from the menu that pops up.

Home console versions followed in 1985 and 1986, but the gameplay is different enough from the 1983 original (strikes being the key addition) to warrant covering those versions separately.

Verdict

There’s a suggestion that the President of Technos Japan wanted to cancel this game halfway through development. He was persuaded otherwise and they ended up with a reasonably-sized hit on their hands, with The Big Pro Wrestling topping Japanese arcade charts in early 1984.

This is a charming snapshop of late 1970s / early 1980s Japanese pro wrestling, packed full of character and nice touches. On one view, it’s a hugely creditable first attempt at the genre featuring intros, larger than life characters, all the top moves of the day, interference and more. However, the gameplay itself gets dull pretty quickly and it cant really be said that The Big Pro Wrestling lays any other gameplay or mechanical foundations for future wrestling games … something that Technos Japan would rectify in their next attempt…